The obstacles to global climate policy

Based on empirical data, a new MCC study describes the driving forces of resistance – and from this derives the political constellation on this great issue of mankind.

In the wake of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the international community has yet to embark on deep decarbonisation pathways. The lack of appropriate measures is not an accident of modern politics, but the result of economic and social constraints that can be objectively measured. For example, a country's oil & gas rents, the extent of corruption, or the basic social trust of the population can all have an influence. This is the starting point of a new study by the Berlin-based climate research institute MCC (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change). The study has now been published in the renowned journal Energy Research & Social Science.

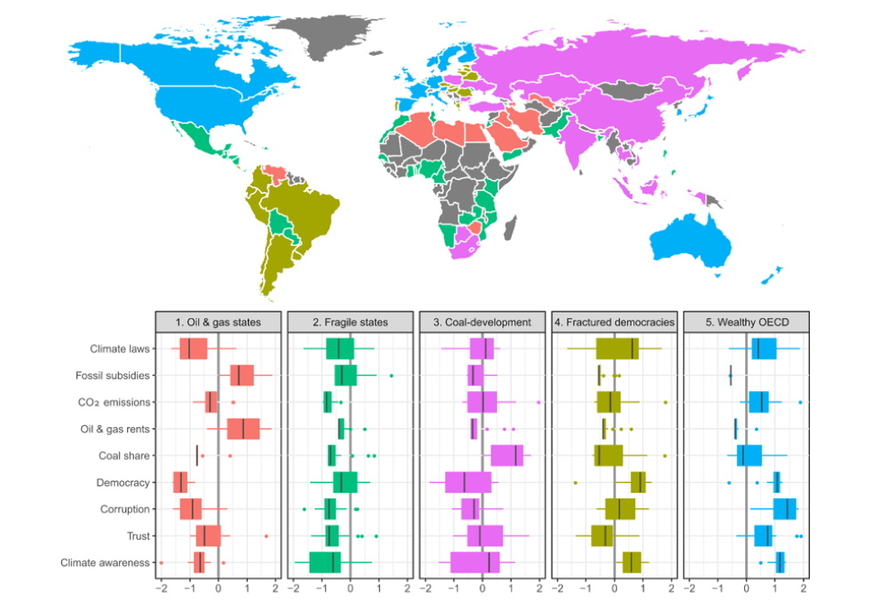

"We outline an architecture of political economic constraints associated with the climate issue, explore which countries are exposed to these constraints, and the extent of that exposure," explains William Lamb, researcher in the MCC working group Applied Sustainability Science and lead author of the study. "Our approach helps us to better understand the tough process of international climate diplomacy.” From a total of nine international statistics and surveys, the authors derive national profiles: the starting positions for climate policy and the performances. Although comprehensive data is not available for every country in the world, the study does provide a conclusive picture for 99 countries, representing 88 percent of the world's population and 92 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions.

"Our systematic correlation analysis shows interesting combinations of constraints," reports MCC researcher Lamb. "A lack of democratic norms often goes hand in hand with exposure to corruption and fossil fuel subsidies. In addition, countries with extensive oil and gas extraction often have autocratic governments and show limited progress on climate legislation.” From the national profiles, the authors develop five clusters of states that are relatively homogeneous in themselves: firstly, oil and gas states; secondly, fragile developing countries; thirdly, emerging economies that are currently heavily dependent on coal; fourthly, fractured democracies that in fact have a relatively high level of climate awareness; and fifthly, rich industrialised countries.

The complete statistics, including the clusters, are provided in a separate file. "Here we have a new, even expandable, empirical research approach with a large information content for political decision makers," emphasises co-author and MCC group leader Jan Minx. “It enables us to feel the pulse of the actors involved, so to speak, to perceive changes and perhaps identify new opportunities for political breakthroughs or strategic alliances at an early stage.”

Reference of the cited article:

Lamb, W., Minx, J., 2020, The political economy of national climate policy: architectures of constraint and a typology of countries, Energy Research & Social Science

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101429